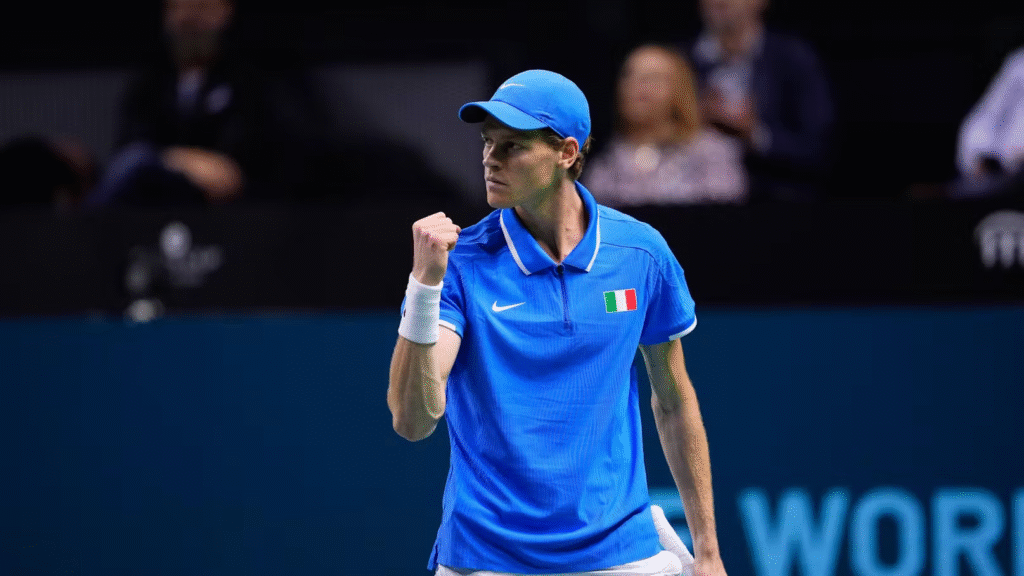

IMAGO/ZUMA Press Wire

In Cincinnati this August, Jannik Sinner walked to his chair, sat down, and shook his head. The Italian, ranked No. 4 in the world and still just 23, could not go on. His retirement midway through a match stunned the crowd, who had paid for tickets expecting fireworks, not an abrupt ending. Some applauded in sympathy, while others booed in frustration, as if his body’s breakdown was a personal slight.

On the other side of the sporting calendar, though no less significant, Ireland’s Rhasidat Adeleke announced she would step away from the remainder of her track season. The 21-year-old sprinter, who had electrified NCAA tracks and carried Irish hopes on her shoulders, was expected to be a headline act at the World Championships. Instead, she chose preservation over performance, citing the need to protect her body and safeguard the longevity of her career.

Different sports, different contexts, but both moments illuminate the same fault line in modern sport. Athletes are caught between two competing arenas: the competition itself, and the expectations of those watching. In one, victory is measured in times, scores, and medals. In the other, it is measured in continuity, reliability, and the ability to show up on demand. When the two diverge, friction follows.

The Irish impact

For Ireland, Adeleke’s decision reverberates beyond her personal career. She is more than just an athlete; she has become a symbol of Irish athletics’ new era, its most visible talent on the global stage. In a country that has struggled to consistently produce world-class track stars since the heyday of Sonia O’Sullivan, Adeleke is seen not just as a competitor, but as a commercial and cultural beacon.

Her absence at the World Championships means more than lost medal chances. It weakens Athletics Ireland’s negotiating power with sponsors, who increasingly tie investment to global visibility. It risks dampening national interest at a time when athletics has been clawing back attention from rugby, football, and GAA. It also complicates government funding discussions. Sport Ireland allocates millions annually, but the spotlight athletes, the ones who draw media coverage and inspire participation, are the ones who justify that investment to the public and to policymakers.

Without Adeleke on the track, Irish athletics loses its headline act at precisely the moment it needed her most. It is not her fault, far from it, but it illustrates the fragile dependence of entire sporting ecosystems on the health of a single individual.

A growing pattern

Retirements and withdrawals have always been part of sport, but their frequency, and visibility, appear to be rising. Part of this is structural: professional calendars are denser than ever, with tennis players facing almost year-round demands, and track athletes often asked to peak multiple times across collegiate, continental, and global competitions. The body can only take so much, and ignoring warning signs is often a fast track to career-ending injury.

Sports science supports this pragmatism. A 2022 study in the British Journal of Sports Medicine highlighted how overtraining syndrome, a mix of chronic fatigue, hormonal disruption, and injury susceptibility, is more prevalent in elite athletes than ever. Muscle fibres subjected to repeated stress without adequate recovery undergo microtears that accumulate into long-term damage. As one leading physiologist put it: “You can push through pain, but you cannot push through biology.”

For Adeleke, the calculation is long-term: step back now, and perhaps add years to her peak. For Sinner, the decision was in-the-moment: push through and risk tearing a ligament or worsening fatigue, or stop and live to fight the next tournament. Both show the shift towards athlete pragmatism.

The economics of absence

Yet to the outside world, absence has a cost. Fans in Cincinnati did not pay to watch Sinner limp off; they paid for spectacle. Broadcasters carved out slots expecting his matches to deliver drama. Adeleke’s withdrawal leaves Irish Athletics scrambling, not only because medals are harder to come by, but because sponsors and broadcasters often tie their investments to marquee names.

The financial implications are significant. A Deloitte report on global sports revenues found that high-profile withdrawals can reduce broadcast audiences by as much as 20 percent, cutting into advertising and sponsorship returns. At the Tokyo 2020 Olympics, broadcasters reported audience dips of nearly 15 percent during sessions where big names pulled out due to injury. For smaller nations like Ireland, those dips can feel seismic.

Ireland does not have a surplus of global track stars. Adeleke’s sprinting brilliance is one of the few major selling points Irish athletics can take to international broadcasters, sponsors, and even grassroots campaigns aimed at getting more children into sport. Her absence is not just a sporting disappointment, it is an economic and cultural one.

Between sympathy and frustration

The response to athlete withdrawals tends to split in two directions. Sympathy recognises their humanity: no body can withstand endless pressure, and stepping away is an act of self-preservation. Frustration, however, sees only the performance missed.

Sinner’s mid-match retirement captured this tension perfectly: applause from some corners, boos from others. Adeleke’s season-ending announcement produced similar divisions in Ireland, admiration for her maturity, but also disappointment that a rising star would not be on the world stage.

This duality exposes the uneasy contract between athlete and audience. Fans want both excellence and reliability, forgetting that the former often undermines the latter. To be spectacular is, by definition, to push limits. But pushing limits makes breakdown inevitable.

The real performance

What these cases underline is that sport today involves two performances. One is on the court or the track, measurable in scores and times. The other is for the audience: an expectation of consistency, of presence, of delivering drama on schedule. The first is human; the second is industrial.

Adeleke and Sinner illustrate how fragile this balance has become. For the Irish sprinter, restraint is a way to secure the future, better to lose one season than to burn out before 25. For the Italian tennis star, retiring mid-match may spare him an injury that derails the rest of the year. Yet in both cases, the very act of preservation is perceived, in some quarters, as betrayal.

Where does sport go from here?

If the trend continues, with more athletes stepping back, retiring mid-match, or opting out of seasons, the sporting world will need to recalibrate its expectations. Governing bodies may need to rethink scheduling to prioritise longevity over constant spectacle. Fans may need to accept that excellence does not always mean availability. And media narratives must shift from framing withdrawals as failures to recognising them as rational, even brave, decisions.

Because the truth is this: the most courageous act an athlete can make is not always to compete, but to stop. Sinner’s bowed head in Cincinnati and Adeleke’s quiet announcement from Dublin both carried the same message: that the body, not the public, gets the final say.

And perhaps, in a culture that increasingly treats athletes as unbreakable, that reminder is exactly what sport needs.